Range Is The New Black - Part IV

Why Developing Range Is the Most Important Thing You Can Do for Managing and Developing Your Career

This next topic brings us to one of the most disruptive and empowering ideas in Range. The idea that sometimes, not being “qualified” is your biggest advantage. Especially when you’re solving a problem no one else has cracked or stepping into a space no one expects you to lead.

Chapter 8: The Outsider Advantage

David introduces us to a surprising insight drawn from science competitions like the InnoCentive challenge. In these competitions, organizations post difficult R&D problems to a global network, inviting anyone, not just internal experts to propose a solution.

You’d expect that the most “qualified” participants would dominate. The people with deep experience in the exact domain of the problem. But that’s not what happens.

In fact, the data show that solutions are most often found by people who are outside the domain entirely, but close enough to understand the problem, and different enough to see it with fresh eyes.

For example, a concrete durability problem posed by a construction company was solved by a chemist. A molecular biology question was answered by someone in computer graphics.

David calls this “cognitive lateral thinking.” It’s what happens when people carry mental models from one domain into another and see things the insiders miss.

Why This Is Vital for Tech Professionals

Let’s now apply this to tech careers, especially in AI-heavy or innovation-driven environments.

Many technical professionals carry deep expertise in a specific stack, system, or architecture. They’ve been trained to solve problems with best practices. But in rapidly changing contexts new product categories, cross-functional initiatives, novel AI use cases best practices don’t exist yet.

The insiders often apply what they already know. But what if the problem requires a completely different frame?

That’s where the outsider shines.

If you’re a software engineer who understands organizational psychology, you might design more human-centered AI products.

If you’re a data analyst who dabbles in regulatory law, you might see compliance risks before legal does.

If you’re a systems architect who studies storytelling, you might communicate infrastructure tradeoffs in a way that influences executives. My last job in tech was that of a systems architect in 2007, way before I l had the opportunity to learn storytelling through a series of other roles I took on after that.

Developing such lateral skills aren’t “side hobbies.” They’re strategic advantages. They are the source of your range.

When Not Knowing the Rules Is Exactly the Point

David explains that many breakthroughs happen when people don’t know what they’re not supposed to try.

He gives the example of Gunpei Yokoi, the inventor behind Nintendo’s Game Boy. Yokoi wasn’t the most advanced engineer. In fact, he worked with “lateral technology” that was not only mature but also used inexpensive components. His genius wasn’t in bleeding-edge tech, but in recombining old parts in new ways.

That’s how he helped turn Nintendo from a playing card company into a global gaming empire.

He didn’t break the rules. He just never learned the ones that kept others stuck.

In the Age of AI, Every Domain Is a Mashup

Modern tech work doesn’t live inside neat categories anymore.

DevOps is blending with security.

ML is merging with design.

Product thinking now includes ethics, trust, and regulatory nuance.

Engineering leaders are expected to understand GTM strategy, pricing, and user behavior.

That means being an outsider in one part of the conversation is inevitable. The question is whether you use that as a constraint or a superpower.

If you’ve ever felt like the odd one in the room too business-oriented for engineering, too technical for marketing, too strategic for ops, then congratulations! That’s your edge.

Practical Strategy: Turn Outsiderness Into Leverage

Own your interdisciplinary background

If you came from a non-traditional path say, economics before engineering, or graphic design before data highlight that. It gives you pattern recognition others don’t have.

Volunteer for ambiguous, cross-functional projects

These are often the ones insiders avoid. But they’re ripe for outsiders to see solutions no one else does. Bring your outside lens to the table.

Study problems in unrelated domains

Find challenges your team is facing and study how other industries solve them. You’ll start to build a library of metaphors, models, and mechanisms that apply across contexts.

Don’t wait for permission

Outsiders don’t always get invited into core decisions. Sometimes you have to show up with a solution first. If you see a blind spot, raise it. If you have an unconventional proposal, pitch it. Respectfully challenge the assumption that “we’ve always done it this way.”

Bottom Line: Your Range is your invitation to what’s next

The next opportunity in your career may not come from what you’ve mastered. It may come from where your strange combination of skills lets you see something others missed.

Being the outsider doesn’t mean you don’t belong. It means you see the game from a new angle.

In a world shaped by rapid change, the outsider is often the innovator. And the person with range is the one who gets to rewrite the rules.

In the next chapter, we’ll go deeper into how seemingly “outdated” tools and experiences can lead to radical innovation when recontextualized creatively.

This chapter takes a curious but powerful turn. David introduces a concept that might sound counterintuitive in a world obsessed with cutting-edge tech and constant upskilling. He argues that old technology, when repurposed laterally, can fuel breakthrough innovation.

It’s not just about chasing what’s new. It’s about seeing what’s useful, even if the world has already moved on.

And for tech professionals navigating the AI age, this chapter has profound implications.

Chapter 9: Lateral Thinking With Withered Technology

The phrase “lateral thinking with withered technology” comes from Gunpei Yokoi, the legendary Nintendo engineer we touched on in the last chapter.

Yokoi didn’t try to build the most powerful hardware. Instead, he embraced outdated components, combined them in unconventional ways, and created iconic products like the Game Boy. While his competitors chased graphics and processing speed, he used cheap, well-understood parts to make games that were simple, fun, and durable.

The Game Boy went on to become a massive global success. Not despite the outdated tech but because of it.

Yokoi’s philosophy was this: when technology matures and stabilizes, it becomes affordable, predictable, and easier to adapt creatively. You can recombine it in new contexts without the risks of bleeding-edge fragility.

That’s lateral thinking. And it works because innovation isn’t always about pushing forward. Sometimes, it’s about looking sideways.

Powering Real World Generative AI Architecture: By Being Boring And Brilliant At The Same Time

In tech careers, it’s easy to become obsessed with “what’s next.” The newest AI model. The latest framework. The next “latest”.

But David’s message, through Yokoi’s story, is simple. You don’t always need to chase the frontier. You can innovate by recombining what already works.

Imagine you’re a senior backend engineer watching your team run out of creative energy. Why?

Everyone around you is chasing the “bleeding edge”: Rust microservices, WASM at the edge, and complex event-driven architectures. On paper, it’s a masterpiece. In practice, the cognitive load is crushing the team. New hires spend weeks just trying to trace a single request through the “event-driven mess,” and the product team hasn’t shipped a meaningful feature in months.

While they hunt for the next shiny framework, you’re looking at your “dated” toolkit: Postgres, Redis, and a battle-tested Monolith.

You realize that creativity isn’t about using the newest tool; it’s about the creative recombination of proven ones. You propose something that sounds almost heretical in a hype-driven office: an internal MVP engine built on a “Boring Technology” stack.

You don’t need a specialized vector database for the new AI feature you know Postgres can handle it with an extension. You don’t need a complex distributed cache for the prototype Redis is already sitting there, ready to go.

The Breakthrough

While the rest of the org is fighting “unknown unknowns” in their experimental stack, your “boring” engine is live in forty-eight hours.

You haven’t just built a prototype; you’ve achieved Operational Maturity overnight. Because you chose a stack where you already know where the “landmines” are buried, you can focus 100% of your creativity on the user experience rather than the infrastructure.

Suddenly, your “outdated” skills are the company’s greatest accelerator. You didn’t win by being the fastest coder; you won by knowing that simplicity is the ultimate sophisticated recombination. You saved the company’s innovation tokens for the product, not the plumbing.

Old Tech + New Context = Strategic Leverage

Lateral thinking with withered technology isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about transference.

You’re using experience with known tools to solve new problems in unfamiliar domains.

And this is where range comes in.

The frontend developer who knows psychology can build interfaces that anticipate user confusion.

The data engineer who’s worked in fintech and education can see patterns that a specialist can’t.

The cloud architect who understands physical logistics can design better infrastructure for distributed systems.

You don’t need the newest thing. You need the right combination of old and new as well as the imagination to apply it laterally.

AI is Built on This Philosophy

Ironically, the entire AI boom is proof of this principle.

The underlying architecture of transformers, which powers GPT and other LLMs, wasn’t invented last year. It came from a 2017 Google paper called “Attention Is All You Need.” And that paper built on decades of earlier work in NLP, probability theory, and gradient descent. If you are interested in this paper, you can find it here on Arxiv.

The magic wasn’t in brand new ideas. It was in recombining known components at the right time, with the right compute infrastructure.

In other words, AI itself is lateral thinking with withered technology.

So if you’re worried that your skills are getting “stale,” ask yourself instead, Where can these tools shine next?

Practical Strategy: Don’t Discard, Reframe

Inventory your “stale” strengths

Make a list of tools, skills, and mental models you’ve mastered that the market thinks are “old.” For each, ask: “Where might this be useful in a new context?” You might be surprised how many doors open when you change the setting.

Recombine before you reinvent

When solving a new problem, start by asking: “What have I used before that might apply here differently?” Don’t reach for new tools by default. Reach for new angles first.

Teach incoming staff the value of the ‘old ways’

Junior engineers might dismiss technologies you know inside out. Show them how reliability, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness still win in many settings. That turns your knowledge into mentorship and range into leadership.

Use constraints as a creativity engine

Don’t wait for unlimited resources. Challenge yourself to solve problems using “low-power” tech. Old methods. Limited compute. That’s how lateral creativity forms.

Bottom Line: The Past Is a Source of Innovation

You don’t need to abandon everything you’ve learned to stay relevant. In fact, the most future-proof professionals aren’t the ones constantly chasing new tools. They’re the ones who can see possibility where others see obsolescence.

Old skills. Legacy systems. Mature tools. These are not liabilities. In the hands of someone with range, they’re ingredients for strategic breakthroughs.

In the next section, we’ll look at an interesting and somewhat contrarian idea “Fooled by Expertise”, where David shows how even the most experienced professionals can be led astray by overconfidence, and why humility is a key part of building effective leadership in a complex world.

This section discussed one of the most cautionary and relevant chapters for anyone navigating complex systems, especially in tech.

This is where David pulls back the curtain on one of the biggest risks in modern careers: overconfidence born from deep expertise. And in a world where decisions must be made across messy, unpredictable, AI-transformed environments, this blind spot can cost more than credibility. It can cost outcomes, influence, and the chance to lead.

Chapter 10: Fooled by Expertise

This chapter opens with a stark and troubling study: Philip Tetlock’s famous 20-year forecasting experiment. Tetlock collected predictions from hundreds of political and economic experts, asking them to forecast real-world outcomes including wars, elections, market crashes.

The results were damning.

The most famous experts, the ones with the highest credentials and deepest specialization performed no better than random chance. Some were worse. Why? Because the more deeply they specialized, the more confident and committed they became to their own frameworks. They filtered out conflicting data. They ignored ambiguity. They rationalized poor outcomes.

The conclusion? In complex, fast-changing environments, narrow expertise isn’t enough. Worse, it can actively mislead.

And here’s the kicker: the most accurate forecasters weren’t the specialists. They were the generalists, the “foxes” (as Tetlock called them). These were the people who knew a little about a lot and were constantly updating their models, cross-checking their biases, and staying curious.

Where do you see this?

Let’s put this in the context of a senior engineer or data leader in 2026.

You’ve spent the last decade mastering a domain — backend infrastructure, enterprise data architecture, ML deployment. You’ve earned your place as the go-to expert.

But now AI models are becoming black-box co-workers. Regulation is accelerating. Security threats are escalating. User behavior continues to shift faster than ever. Consider this: People don’t “Google” for information anymore, they “ChatGPT” or “Gemini” etc for answers. Subtle but highly nuanced behavior disrupting the whole ecosystem and business models build on Search Engine Optimization. Bringing us back to you as the data leader or the senior engineer we started to talk about, your leadership is suddenly expected to extend beyond your area of technical comfort. And why is it that you are expected to do that? Because emerging technologies create emerging landscapes and emerging multi-domain problems that hardly anyone is an expert to solve for.

In this moment though, overconfidence can become a career-limiting condition.

You insist a new system can’t scale, because it doesn’t follow traditional sharding best practices.

You dismiss an AI product idea because it doesn’t fit your model of “real ML.”

You push back on design trade-offs because they conflict with your engineering instincts, not because you’ve tested outcomes.

And slowly, you become less effective, not more. Because your deep domain expertise starts blinding you to a changing landscape.

The AI Age Demands Humble Leaders

This is one of the central arguments David makes. In wicked environments where rules change, data is incomplete, and feedback is delayed the best decision-makers are humble, adaptable, and multidisciplinary.

In other words, they have range.

They are not the loudest voice in the room. They’re the ones asking questions. Testing assumptions. Borrowing models from other fields. Updating their priors based on new evidence.

In Tetlock’s research, these “foxes” were:

More likely to acknowledge uncertainty.

More open to input from outside their domain.

More likely to change their mind.

More accurate over time.

If you want to lead in AI, where no one can be an expert in everything, this mindset is non-negotiable.

Real-World Parallel: The 2008 Financial Crisis

David ties the lesson of expert overconfidence to the 2008 crash. Many of the so-called smartest financial minds PhDs, Nobel laureates, quants were completely blindsided by systemic risk. Their models, which had worked in predictable environments, failed in reality.

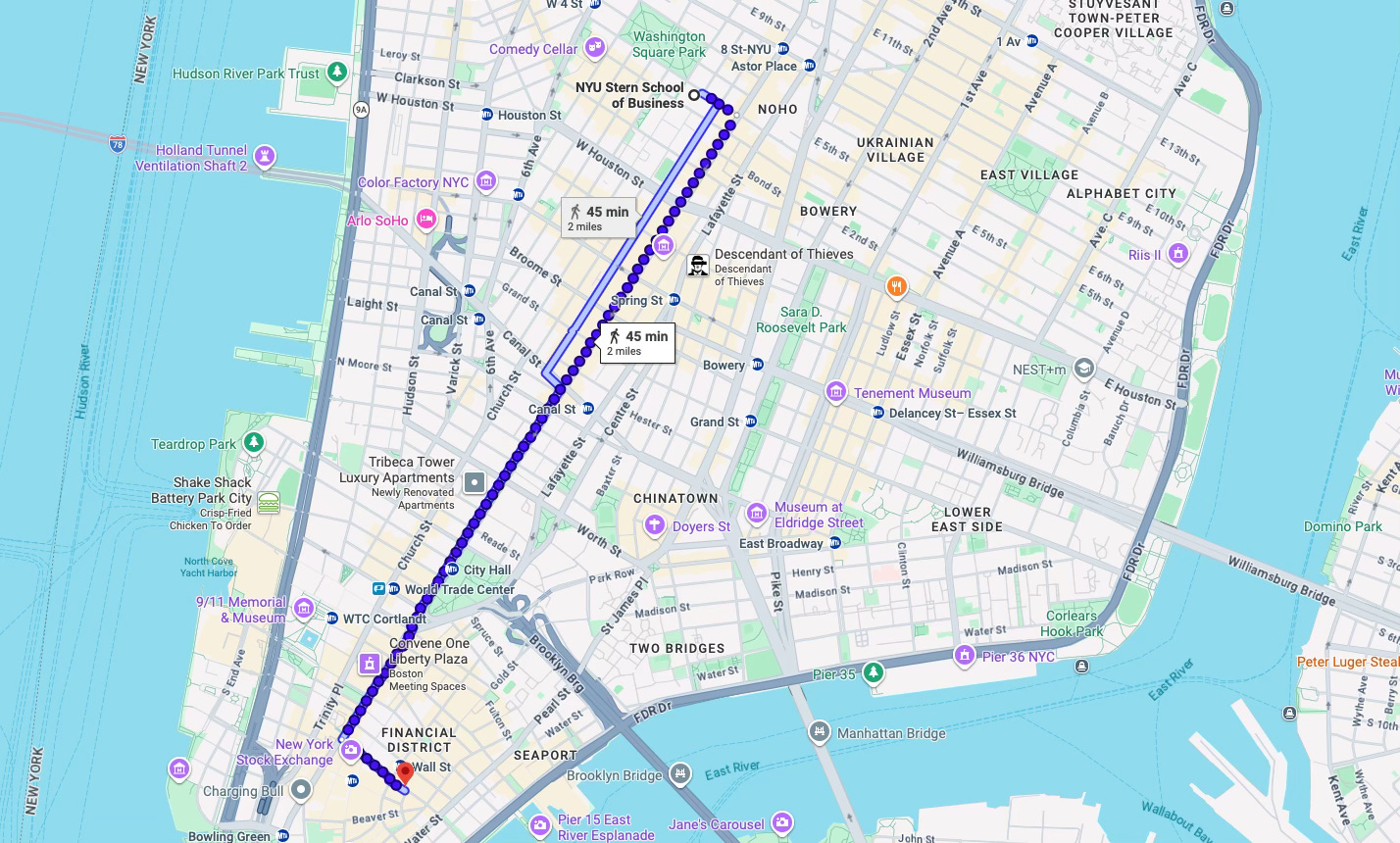

During my days at B-school, I recall being in a class in 2009 at NYU Stern where I was sitting next to a classmate who had previously graduate from MIT with a degree in engineering. She worked as quant at a leading rating agency in the city. She validated this exact point for me we were hearing in the media - “No industry insider seemed to have seen this coming”. This whole crisis seemed closer to home for us given its recency, its continuing fall out, and more so because we were in a classroom about two miles from the epicenter of this meltdown. (Map below).

But who saw the crisis coming? Often, it was outsiders journalists, generalist investors, or people who cross-referenced multiple fields. People who saw the connections others missed. People who questioned the sacred models.

The analogy to AI-driven tech is clear. Many of the best decisions won’t come from specialists. They’ll come from people who know just enough across multiple domains to spot the disconnects.

Practical Strategy: Adopt a Fox Mindset

Regularly update your frameworks

Don’t cling to the same decision-making playbook forever. Create a habit of reevaluating your assumptions quarterly. Ask, “What has changed in the environment that should change how I think?”

Invite contradiction

Seek out voices that disagree with you including other teams, backgrounds, or functions. Encourage dissent in your meetings. This doesn’t weaken your authority. It strengthens your decisions.

Cultivate humility

Get comfortable saying “I don’t know yet.” It’s not weakness. It signals intelligence in complex environments. Model this for your teams.

Study other disciplines

Learn how strategists, product designers, psychologists, and historians think. You’ll start seeing failure patterns and solution patterns your peers overlook.

Test small, iterate fast

Avoid placing big bets based solely on confidence. Set up small experiments that generate real data. That’s how foxes build confidence not from belief, but from feedback.

Bottom Line: Don’t Let Your Strength Become Your Limitation

In a world where AI is changing the rules faster than we can codify them, being “the expert” is less valuable than being the adaptable thinker.

Yes, your experience matters. But your range: your ability to integrate diverse models, admit uncertainty, and adjust will determine how far you go.

The best leaders in the AI era won’t be the most confident. They’ll be the most curious.

In the next section the cautionary tone develops into signaling of danger which in my opinion is highly relevant for tech professionals as well. David explores why professionals often fail when they refuse to let go of legacy ways of thinking and how this affects real-time decision-making under stress.

If the last chapter warned us about the dangers of overconfidence, this one delivers the natural follow-up: What happens when we cling to the tools, methods, and models we know even when the world changes around us?

David makes a compelling case that failing to drop familiar tools isn’t just inefficient can be deadly. For tech professionals navigating rapid change, that’s not a metaphor. That’s a roadmap for irrelevance, unless we develop the muscle to adapt.

Chapter 11: Learning to Drop Your Familiar Tools

David draws from a tragic and powerful example: firefighting disasters, specifically the 1949 Mann Gulch fire that killed 13 elite smokejumpers. The men who died weren’t untrained or underqualified. In fact, they were some of the best in the business.

So what happened?

When the fire turned unexpectedly, they were instructed to drop their tools and run uphill. But many couldn’t do it. They clung to their heavy equipment including shovels, saws, packs. These tools that had become symbols of identity and control. Tools that made them feel like professionals.

They slowed them down. And they died.

In later incidents, it happened again. Highly trained responders failed to abandon familiar tools, even in life-threatening scenarios. Why? Because tools aren’t just objects. They’re extensions of self. Dropping them felt like dropping identity.

The result? Inflexibility in the face of change. Tragedy in the face of speed.

What This Means for Tech Professionals

In tech, our tools are usually digital. But our emotional attachment to them is just as real.

The framework you’ve used for years.

The data model you built from scratch.

The codebase you’ve maintained like a second brain.

The process you refined and defended over time.

These aren’t just tools. They’re symbols of mastery. Of credibility. Of who we are as professionals.

Which is exactly why they’re so hard to let go of—especially when the terrain shifts. Especially when AI changes the very assumptions those tools were built on.

Dropping Familiar Tools in the AI Era

Let’s make this painfully real.

Imagine you’re a seasoned DevOps engineer. You’ve spent a decade hand writing YAML files., meticulously hand-crafting CI/CD pipelines and mastering the art of containerization with Kubernetes. You were the “gatekeeper of production.”

Then, the Abstraction Wave hits. Enter Vercel.

New AI-native deployment platforms emerge that don’t just assist you they commoditize your core tasks. They handle auto-scaling, blue-green deployments, and secret management with a single prompt. 80% of your “hard-earned” expertise is suddenly a background process.

The Pivot

You face the classic “Engineer’s Dilemma”: do you fight the tool by pointing out its edge-case failures, or do you treat the tool as a new primitive?

You choose to evolve. You stop being the “plumber” fixing individual leaks and become the Architect of Velocity. You realize that while the AI can deploy the code, it doesn’t understand System Resilience, Compliance, or Cost-Efficiency.You can resist it, dismiss it, argue its limitations. Or you can learn the new system, drop some of your old tools, and evolve into a new kind of builder: someone who enables velocity through orchestration, abstraction, and systems thinking.

Now multiply that across roles:

The data scientist who lets go of manual feature engineering in favor of AutoML, and pivots toward interpreting models in business context.

The engineer who drops custom microservice sprawl and embraces platform thinking, improving performance by simplifying instead of scaling.

The PM who gives up a strict agile cadence in favor of continuous experimentation based on AI feedback loops.

In all of these examples, professionals grow not by clinging, but by releasing.

This Isn’t About Abandonment. It’s About Reframing.

Dropping familiar tools doesn’t mean throwing away your value. It means updating how your value gets expressed.

It’s the database wizard who becomes the real-time observability expert.

The cloud infrastructure builder who becomes the systems reliability strategist.

The brilliant coder who becomes a tech translator for the C-suite.

You’re not starting over. You’re moving up.

Practical Strategy: Build Your Adaptation Reflex

Inventory your identity tools

Ask: “Which tools, methods, or models do I deeply associate with my professional identity?” These are the hardest to drop. And the most important to question.

Run “no tool” challenges

Once a quarter, try solving a common problem without your go-to tool. Force a constraint. It’ll surface blind spots and make space for lateral solutions.

Welcome junior insight

Junior team members often adopt new tools faster because they’re less invested in legacy ones. Learn from their freshness. It’s not just naivety, it’s agility.

Decouple ego from method

Your value isn’t tied to any one tool. It’s tied to your ability to solve real problems. Focus your pride there.

Create exit strategies for old methods

Build a habit of retiring tools, not just accumulating them. What do you no longer need to carry? What’s slowing you down?

Bottom Line: Adaptation Is a Leadership Skill

In high-velocity environments, those who succeed aren’t the ones who hold the tightest grip. They’re the ones who can let go when the moment demands it.

In firefighting, that reflex saves lives. In tech, it saves careers.

Range is what helps you build that reflex. Because when you’ve experimented across domains, roles, and perspectives, you’re less attached to any single tool. You trust your ability to adapt, not your ability to defend.

And that’s what future-ready professionals do. They don’t define themselves by their tools. They define themselves by the problems they’re ready to solve.

In the final section named Deliberate Amateurs, we explore how embracing the amateur mindset: curious, flexible, unburdened by expert baggage can make you not just more innovative, but more influential.

If this helped you reframe your thinking about your career development please consider sharing with others. (And, feel free to post it to your LinkedIn network).

More content like this in the future. Stay tuned.

If you missed the previous posts. They can be found here:

Part I is here.

Part II is here.

Part III is here.